Russia-Iran Strategic Partnership Treaty Highlights Bilateral Priorities

Recent Articles

Author: Nigel Li

01/28/2025

Russia and Iran have intensified cooperation in recent years in the face of increased confrontation with the West, most recently seen in their newly signed comprehensive strategic partnership treaty. On January 17, Russia’s President Vladimir Putin met with his Iranian counterpart, President Masoud Pezeshkian, in Moscow, to sign what purports to be a grand bargain between the two countries. However, the recently inked agreement appears to re-formalize many existing bilateral processes without offering much, if anything, groundbreakingly new. Despite recycling of older protocols, the treaty does serve as a clear demonstration of Russia-Iran intent and convergence in areas such as economic integration, nuclear technology sharing, and joint military exercises. Because both countries are sidelined from many global trading regimes, the new partnership appears more a marriage of convenience and isolation. However, there remain significant challenges that both Moscow and Tehran must overcome, if they are to reap any real benefit from cooperation.

Regional Assertions

Articles 12-14 of the new treaty declare they will, among other regions, promote stability and peace in Central Asia and “Transcaucasia,” even though countries of those regions are not signatories to the agreement. Caspian littoral states Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan are familiar with the treaty’s wording seeking to prevent “interference” by third states in the region, because it is reminiscent of past language and efforts used by Russia and Iran to control energy, independent transit, and trade across the Caspian. The treaty clauses reference the Caspian “zone,” as it is mentioned in the Caspian Sea Treaty of 2018, that tended to favor Moscow and Tehran’s political and economic ambitions.

Bilateral Reassurances

One notable article of the new treaty bars either party from taking “unilateral coercive measures” which would be deemed an “unfriendly act” against the other. This provision, for instance, could impede either country from one-sided actions in pricing oil to sanctions-sensitive markets. The article also notes that each party should refrain from joining unilateral coercive measures from third countries that target either Russia or Iran, binding both to shared global fates. Additionally, the treaty is valid for 20 years with automatic extensions for subsequent five-year periods.

There are unique aspects of the document, distinguishing it from Russia’s 2024 treaty with North Korea. That agreement also included a broadly defined indefinite mutual defense clause. In contrast, the Moscow-Tehran treaty is far more measured and pragmatic, refraining from collective security guarantees. More a formalized confirmation on the existing state of current relations, the treaty features no binding obligations between the two countries and, instead, offers aspirations and intentions.

Energy Cooperation

At the Putin-Pezeshkian summit, the Russian leader also mentioned that Russia plans to deliver up to 55 billion cubic meters of gas per year to Iran. Russia’s Gazprom and the National Iranian Oil Company signed a $40 billion memorandum of understanding in July 2022, to develop the Kish and North Pars gas fields along with six other oil fields. Once, Russia and Iran were natural competitors in the hydrocarbon market. But since the war in Ukraine, Moscow has had limited investment options and turned to Iran as an energy partner and hydrocarbon export destination.

Alleviating Infrastructure Bottlenecks

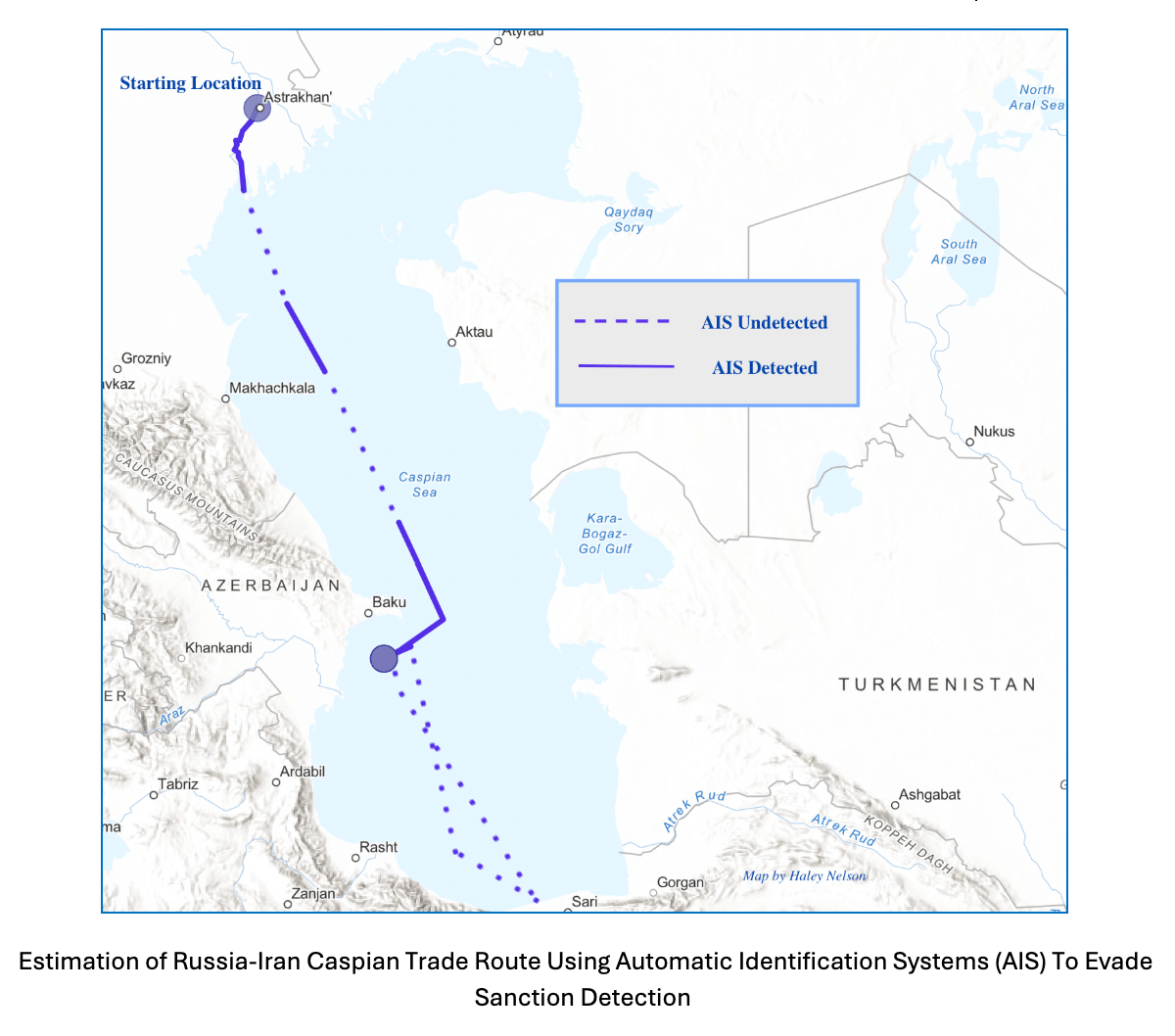

The Caspian Sea, referred to in the treaty as a “zone of peace, good-neighborliness, and friendship,” intends to be a critical trade corridor for Russia and Iran. Following the signing of the treaty, Putin boasted of the “great prospects” for the development of the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC). The trade route spans 7,200 kilometers (4,500 miles) linking Russia to India across the Sea as well as via Azerbaijan and through Iran. Moscow has focused greater attention on this project as it seeks to circumvent traditional routes through Europe to avoid Western sanctions.

The INSTC aims to shorten the transit of freight from Russia to India from 45 days to 15 days, though in reality this seems unlikely. The January 10 U.S. sanctions on 183 tankers transporting Russian oil to India and China, on top of the 2024 sanctions on 139 tankers carrying illicit Iranian oil, places restrictions on the movement of sanctioned ships and their sanctioned cargoes from these ports.

The INSTC aims to shorten the transit of freight from Russia to India from 45 days to 15 days, though in reality this seems unlikely. The January 10 U.S. sanctions on 183 tankers transporting Russian oil to India and China, on top of the 2024 sanctions on 139 tankers carrying illicit Iranian oil, places restrictions on the movement of sanctioned ships and their sanctioned cargoes from these ports.

Currently, the route faces a major bottleneck when it reaches Iran. This is due to decades of sanctions and lack of investment in modernizing Iran’s infrastructure. Almost half of the country’s 900 locomotives are inoperable due to the lack of resources and the inability to acquire components for repairs. Iran aims to link it rail hub on the Azerbaijan border to the Indian Ocean, adding 1000s of kilometers of new track that would connect to vital ports on the Arabian Sea, although unfinished rail projects litter the country. Unimplemented construction agreements, lack of financing, and crippling U.S. sanctions are significant impediments to INSTC’s ambitions objectives.

Nevertheless, the treaty calls for greater cooperation in developing the INSTC and encouraging the use of the transport corridor by third countries. Moreover, relying solely on Russian infrastructure investment, it is doubtful that Iran can alleviate the logistical bottlenecks in the country. For instance, Russia’s 1520mm-gauge railways are incompatible with Iran’s 1435mm-gauge railway. While it is possible to transfer cargo from one railcar to another, this would further slow transit times and create safety hazards when handling certain materials such as liquid cargo.

Financial Integration

One of the priorities expressed in the treaty was to develop a payment system “independent of third countries” to implement bilateral settlements in national currencies, further insulating Russia and Iran from Western financial sanctions. Russia and Iran are ranked, respectively, the top two most heavily sanctioned nations, which has stifled their ability to trade internationally. This effort could advance Russia’s strategic ambitions to consolidate the Eurasian economic space. Already in December last year, Iran was granted observer status in the Moscow-backed Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) after signing a free-trade agreement with the organization. The trade agreement, when implemented, will eliminate tariffs between Iran and Russia for most trade goods, thereby stimulating trade betweent he two and harmonizing payment systems.

Nuclear Cooperation

Russia’s state-run Rosatom is currently supporting the construction of two new units of Iran’s Bushehr nuclear power plant. While the treaty broadly supports further cooperation on the peaceful use of nuclear energy, Russia’s support of Iran’s civilian nuclear industry has been long-standing.

With Russia’s last gas pipeline to Europe now shut down, and with more sophisticated sanctions targeting Russia’s oil-carrying “shadow fleet,” Moscow might be more willing to export its nuclear technology to willing nations as a source of crucial revenue. Unlike oil and gas contracts, nuclear deals are far more long-term, requiring not only the technology but also a consistent pool of nuclear experts able to operate facilities.

The treaty’s clause on refraining from applying “unfriendly coercive measures” (i.e. sanctions) could complicate the ability for collective pressure on Iran to be effective. But by remaining strategically relevant, Moscow mitigates the possibility of being sidelined in a bilateral U.S.-Iran deal - a plausible scenario with the return of President Donald Trump. While concerns that Iran may develop nuclear weapons are not unfounded, Moscow’s nuclear cooperation with Tehran seems unlikely to create proliferation risks.

Predictability is what matters

Putin and Pezeshkian signed a treaty that does little to present anything new, but it is precisely the predictability of the agreement that reveals a relationship that is built on mutual necessity and interest. The treaty could heighten anxieties in Western capitals of the emboldened “axis” in Eurasia, but the new administration in Washington might present options for either Russia or Iran that could create divergent interests. Pezeshkian concluded during the press conference that the agreement is an “impetus and stimulus towards building a multipolar world.” As much as the next years may test America’s leadership, it will also be a test of the staying power of an alternative multipolar vision.