The Minerals that Make our Military: Strategic Opportunities in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Ukraine

Recent Articles

Author: Joshua Bernard-Pearl

09/18/2024

This is the third installment in the Caspian Policy Center’s Strategic Minerals series, exploring what materials are needed for defense technology and how Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Ukraine could become key players in supplying this national security necessity.

In the high-stakes world of defense technology, the United States faces a glaring vulnerability--a dangerous overreliance on China for strategic minerals. These materials are crucial for advanced weaponry and cutting-edge tech and are also the backbone of U.S. national defense and economic resilience. In the words of U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin, “Strategic and critical materials are vital to our national defense and economic prosperity, enabling the United States to develop and sustain emerging technologies.” By leaning so heavily on China, America risks crippling its own security in the event of conflict.

As a result, there is increased reason for the United States to pay attention to the relatively undeveloped strategic resources of Central Asia, the Caucuses, and Ukraine in order to de-risk its vulnerable supply chain. These regions are brimming with essential resources like rare earth elements, titanium, and gallium, which are critical for everything from night-vision goggles to precision-guided munitions. By pivoting to sources in Central Asia, the Caucuses, and Ukraine, the United States could break free from its China dependency, fortify its supply chains, develop new and strategic partnerships, and reclaim control over its technological and defense capabilities. A robust strategic minerals trade relationship with this trio of partners would also help meet a second U.S. defense-related interest. It strengthens the region’s connectivity and provides a source of economic independence from Russia, diminishing Russia’s global influence and promoting American soft power.

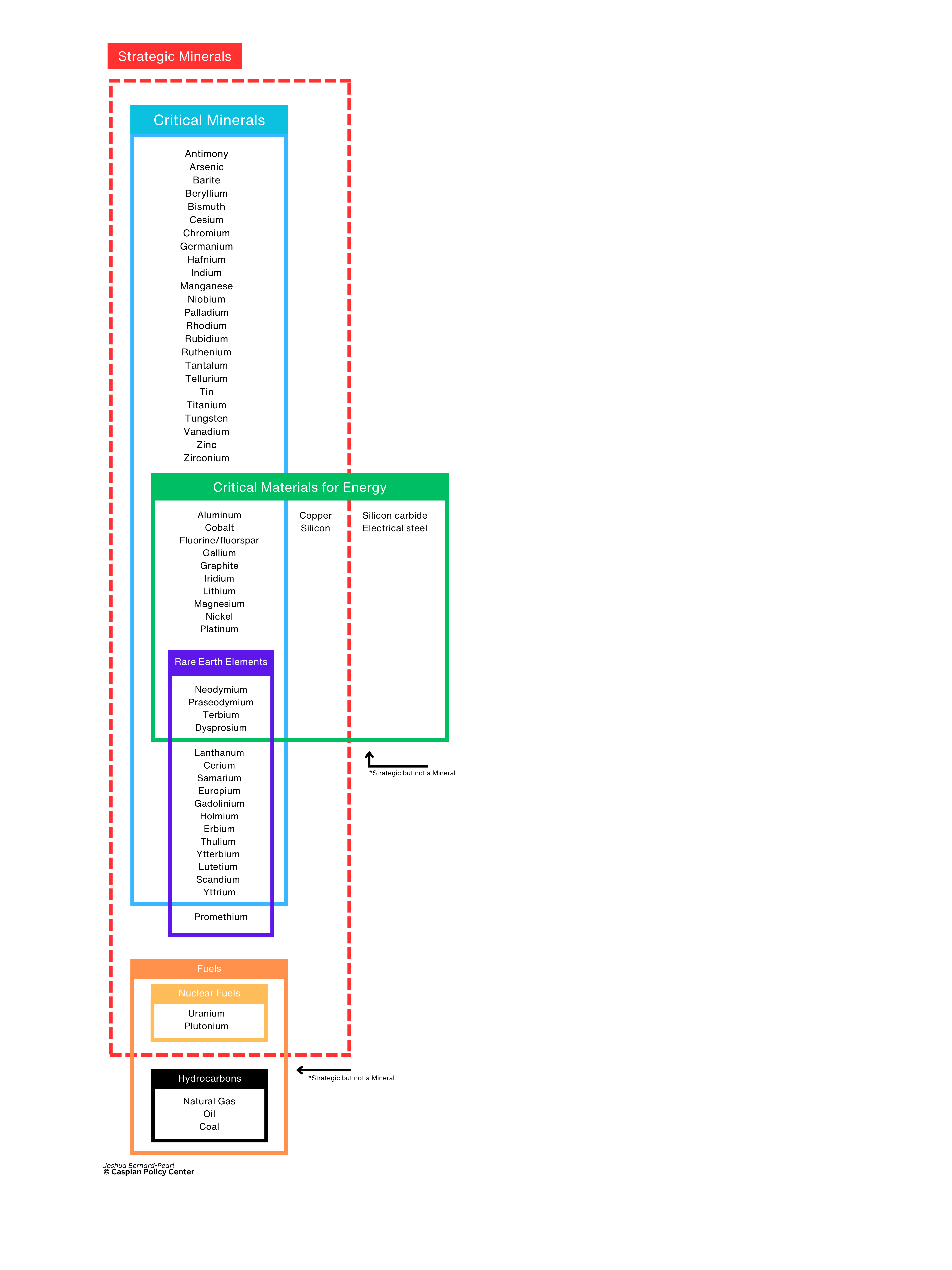

To understand how these minerals can aid the U.S. defense industry, one must understand just what is a “strategic” or “critical” mineral, because there are differing definitions. The United States Geological Survey (USGS) lists 50 minerals as “critical minerals,” defined as non-fuel minerals that are “essential to the economic and national security of the United States” and “the supply chain of which is vulnerable to disruption.”

This list includes a number of minerals crucial to U.S. strategic needs, but several other official lists also exist, including the “critical materials for energy” list from the Department of Energy (DOE). The Department of Defense also produced a list of 250 “Strategic and Critical Materials”; however, this list differs from the “critical minerals” list because it also includes downstream products and focuses on the manufacturing processes that are not relevant to the extraction or refining of the base minerals.

This article looks at strategic minerals as defined by a combination of the USGS critical minerals list, the minerals included in DOE critical materials for energy list, all rare earth elements, and nuclear fuel minerals in order to focus solely on the first step in the complex supply chains behind U.S. military technology.

Advanced semiconductor chips are a crucial component of any modern military equipment. These chips are used in almost every weapons system from drones to missiles to submarines. The importance of this technology has been especially highlighted over the past two and a half years through the extreme lengths Russia has gone through to secure semiconductors for its war in Ukraine by importing thousands of large appliances and other dual-use technologies just for their chips in order to circumvent sanctions.

These chips require over 300 materials to produce, including a number of notable strategic minerals. Silicon, germanium, gallium, and arsenic are the most widely used semiconductor materials. Kazakhstan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan all contain reserves of silicon. Kazakhstan is currently the 10th largest producer of silicon in the world, while Ukraine was the 13th largest exporter in 2021.

Ukraine is also the world’s fifth-largest gallium producer, a potential counterbalance to China’s virtual monopoly on this mineral’s production and its export restrictions of this vital circuitry element for advanced guidance systems. Crucial to infrared and other technologies, reserves of germanium exist in Uzbekistan but have yet to be exploited. China has also moved to restrict exports of this element.

Semiconductor chips also make use of cobalt and palladium, as well as rare earth elements scandium, titanium, and fluorite, for various components. All of these elements have deposits within Central Asia, the Caucuses, or Ukraine. Without semiconductor chips, not a single advanced weapons system would be able to function. Without a secure supply of minerals to produce these chips, all of the infrastructure and investment capital the United States has put into the manufacturing process through initiatives like the historic chips and science act will be futile.

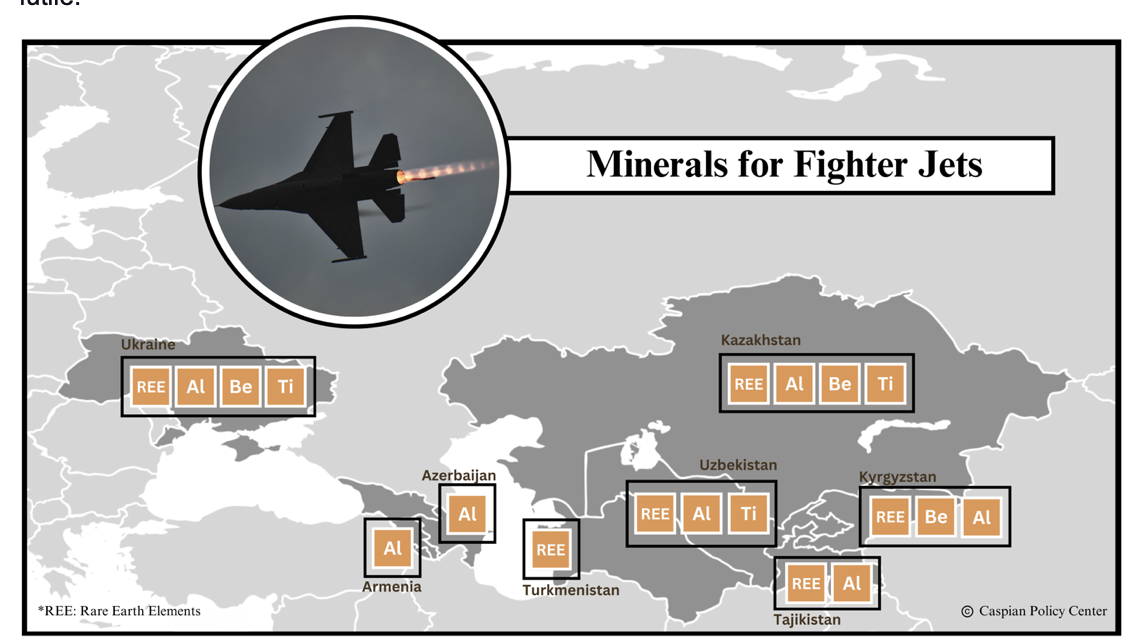

In addition to computer systems, countless strategic minerals are used for their strength, durability, and unique properties in the mechanical components of most noteworthy weapons systems. For example, various rare earth elements are used to manufacture jet engines, while 80% of aircraft, including the F-16 fighter jet, are made from aluminum. Moreover, titanium and beryllium are also used and crucial for their durability, heat resistance, and lightweight properties in aircraft.

In addition to computer systems, countless strategic minerals are used for their strength, durability, and unique properties in the mechanical components of most noteworthy weapons systems. For example, various rare earth elements are used to manufacture jet engines, while 80% of aircraft, including the F-16 fighter jet, are made from aluminum. Moreover, titanium and beryllium are also used and crucial for their durability, heat resistance, and lightweight properties in aircraft.

Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine all hold substantial deposits of rare earth elements (REEs), with the Central Asians all launching initiatives to increase production over the past four years. In 2023, Kazakhstan was the fourth-largest producer of titanium in the world, producing approximately 16,000 metric tons. Ukraine likewise has significant reserves, estimated by the United States Geological Service in 2022 to contain 8.4 million metric tons of ore, which is 1.12% of the world’s titanium reserves. Other estimates have claimed that unexplored reserves bring that number up to 10% for this element vital to the production of modern aircraft.

Kazakhstan is likewise an important source of beryllium, containing one of only three beryllium production facilities in the world and producing 25% of the global supply, according to the Kazakh Minister of Industry and Construction. Aluminum is also abundant with reserves found in almost every country across Central Asia.

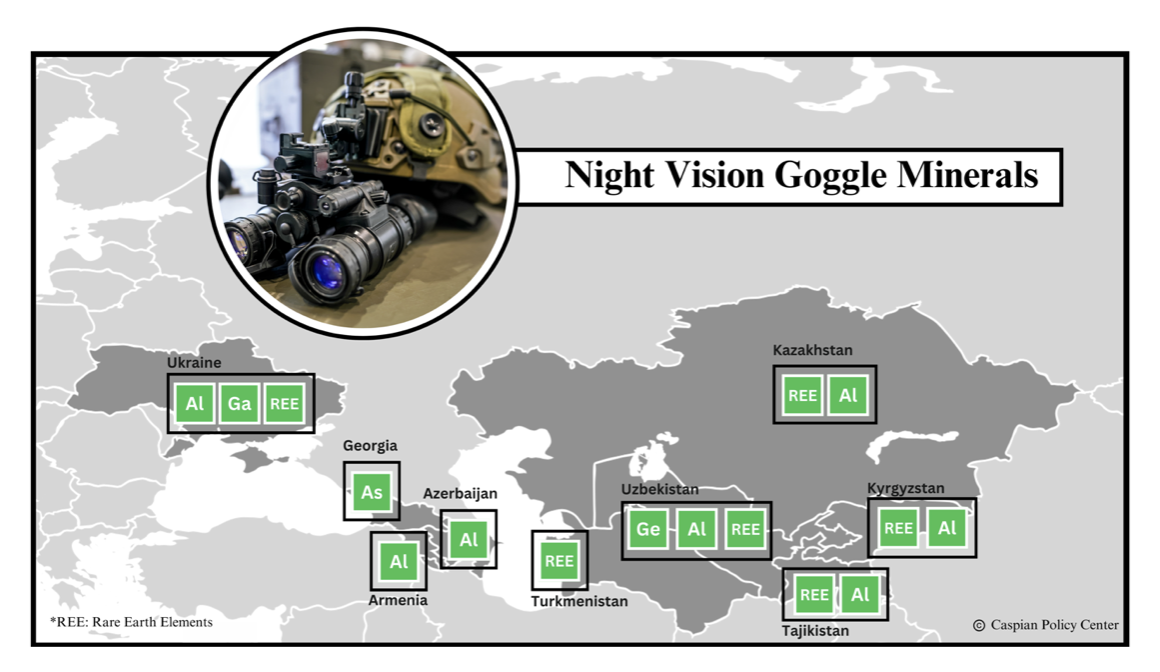

In addition to large military machinery, strategic minerals are just as necessary on a smaller scale in the personal equipment of soldiers. Some examples include nickel for body armor; aluminum, manganese, chromium, and vanadium used in the M4 Carbine rifle; or aluminum, gallium, arsenic, germanium, and other Rare Earth Elements used in night-vision goggles. Kazakhstan is a dominant producer of both chromium and manganese. The country is the second-largest producer of chromium with 95% of the world’s reserves, and contains the second-largest reserves of manganese, estimated at 600 million tons. Ukraine and Georgia are likewise notable suppliers of manganese, producing ore with 600 thousand and 224 thousand metric tons of manganese content respectively in 2021.

In addition to large military machinery, strategic minerals are just as necessary on a smaller scale in the personal equipment of soldiers. Some examples include nickel for body armor; aluminum, manganese, chromium, and vanadium used in the M4 Carbine rifle; or aluminum, gallium, arsenic, germanium, and other Rare Earth Elements used in night-vision goggles. Kazakhstan is a dominant producer of both chromium and manganese. The country is the second-largest producer of chromium with 95% of the world’s reserves, and contains the second-largest reserves of manganese, estimated at 600 million tons. Ukraine and Georgia are likewise notable suppliers of manganese, producing ore with 600 thousand and 224 thousand metric tons of manganese content respectively in 2021.

The current strategic minerals landscape reveals a pivotal opportunity for the United States to reshape its defense industry’s future. Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Ukraine emerge as indispensable partners in this transformation, offering a wealth of resources critical to maintaining American technological and military superiority. Although the complete mineral requirements of the U.S. military is not publicly available information, anecdotal technologies reveal that the minerals required are diverse and expansive. A secure and abundant supply of strategic minerals is necessary to keep American technology dominant, American weapon systems operational, and American soldiers safe and properly equipped.

The current strategic minerals landscape reveals a pivotal opportunity for the United States to reshape its defense industry’s future. Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Ukraine emerge as indispensable partners in this transformation, offering a wealth of resources critical to maintaining American technological and military superiority. Although the complete mineral requirements of the U.S. military is not publicly available information, anecdotal technologies reveal that the minerals required are diverse and expansive. A secure and abundant supply of strategic minerals is necessary to keep American technology dominant, American weapon systems operational, and American soldiers safe and properly equipped.

By diversifying its supply sources and tapping into the rich mineral deposits of these regions, the United States can not only secure its defense capabilities, but also reinforce its geopolitical stance through partnerships in these three regions. This strategic realignment promises not just a fortified defense infrastructure, but a strategic advantage that can shift global power dynamics. Embracing this potential will ensure that America remains at the forefront of military innovation while fostering stronger international alliances and American influence. The path forward is clear: by investing in these emerging mineral powerhouses, the United States will safeguard the production of critical defense technology against China’s near monopoly of mineral refining and export restrictions on these vital materials.