Merging the Ecological and Trade Challenges of the Caspian

Recent Articles

Author: Jahan Taganova, Nathan Hutson, Rachana Mattur

12/14/2023

shutterstock

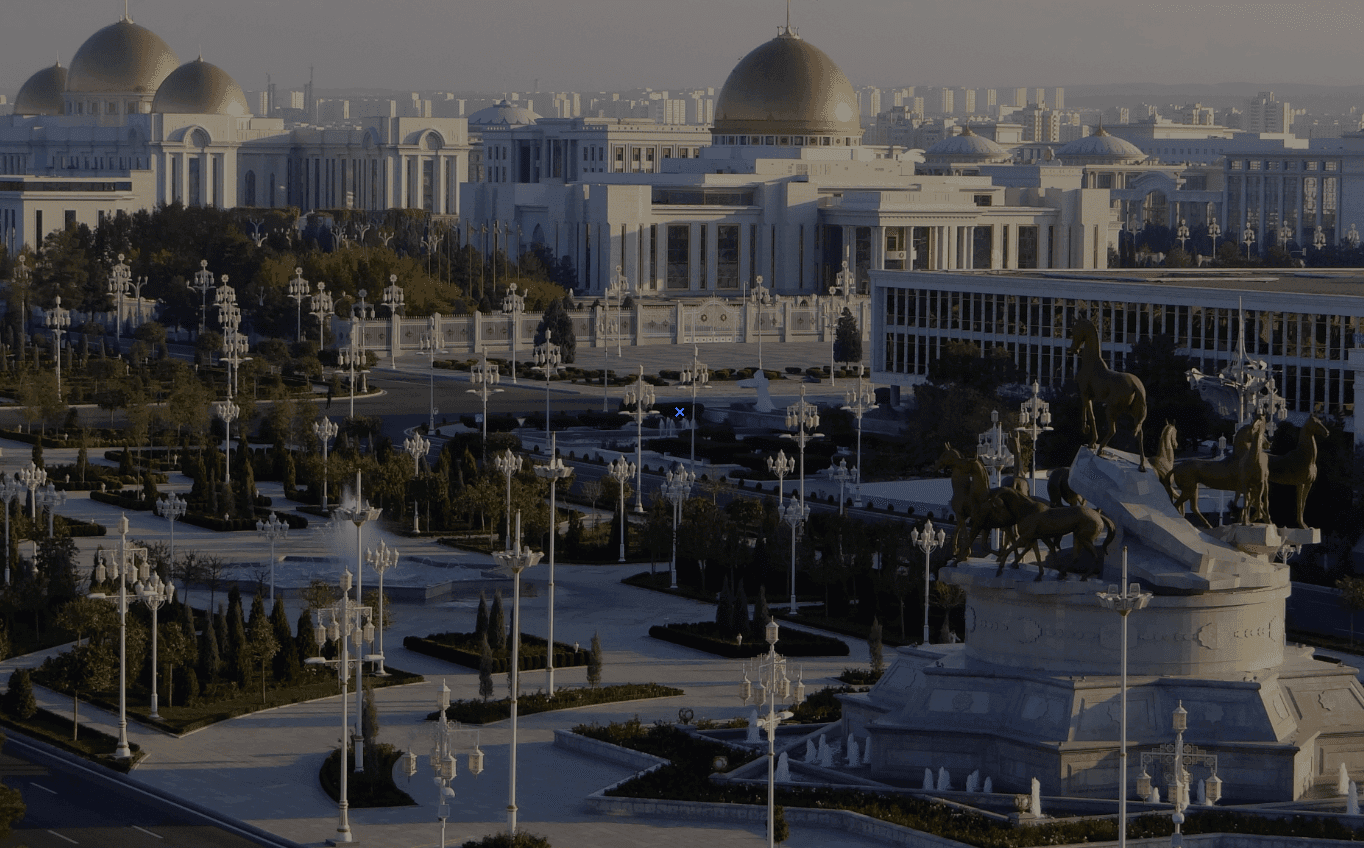

shutterstockA looming shortage of potable water driven by rising global temperatures and poor water resource management threatens the stability of Central Asia. The vital Amu Darya River’s water supply is estimated to be reduced by more than half by 2060, whereas the Khauz-Khan reservoir in Turkmenistan now covers only 75.4 square kilometers from its capacity of 210. Further complicating matters, Afghanistan's Taliban government is completing the 285-kilometer Qosh Tepa Canal, which will allow the Islamic Emirate to draw water from the Amu Darya River for the first time, greatly exacerbating the shortage. Based on the depletion of the Amu Darya River volume, the government of Uzbekistan published an unprecedented presidential decree on water conservation, followed by an additional emergency declaration in November.

For these reasons, desalination of Caspian seawater has emerged as a proposed solution to enhance water supplies for domestic and municipal use. Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan are already desalinating Caspian seawater as a response to their own water shortages; Kazakhstan plans to build an additional nine desalinization plants, while Iran and Turkmenistan have also been considering building new desalination plants along their respective coasts.

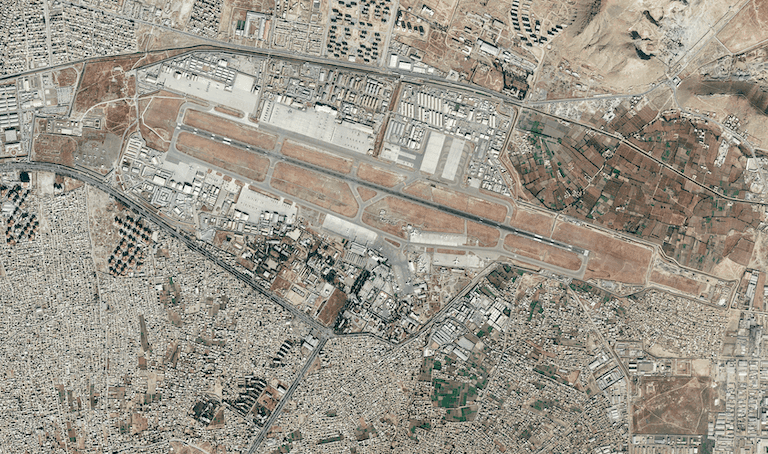

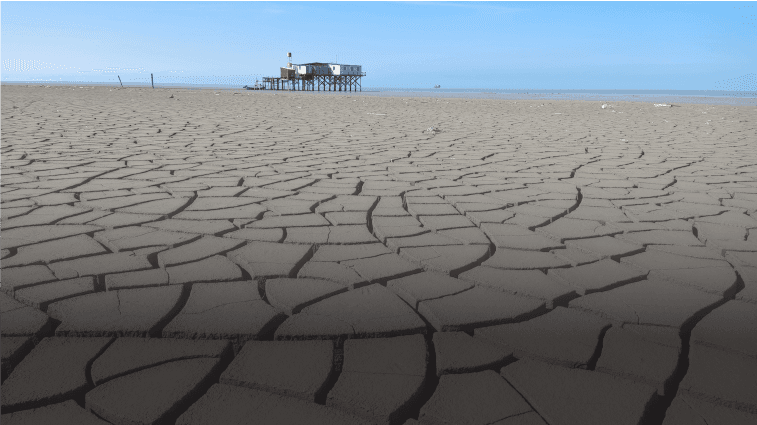

Nevertheless, the Caspian Sea, one of the world’s largest inland water bodies and crucial to the economies of five states, is itself experiencing an indisputable and accelerating decline in water levels, which will imperil local economies, quality of life, and regional commerce. If left unchecked, these desalination projects have the potential to exacerbate and accelerate the depletion of the Caspian Sea. Kazakhstan's Garysh Sapary National Space Agency revealed that Kazakhstan's portion of the Caspian Sea decreased by 7.1% from 2008 to 2023. Similarly, on May 29, 2023, RFE/RL's Turkmen service reported a 35-40 cm drop in water level along Turkmenistan's Caspian coast. Despite the historic reticence of regional leaders to create alarm over environmental issues, the severity of the problem is beginning to change this approach. For example, due to the Caspian Sea's receding waters, Kazakhstan's coastal city of Aktau declared an emergency on June 7, 2023 - marking a shift in the Kazakh government’s environmental discourse, which had previously been reluctant to acknowledge the problem's existence.

While the falling level of the Caspian is only one aspect of Central Asia and the Caucasus’ multifaceted water crisis, solving the Caspian water crisis may create a forum of international cooperation that pays dividends for related coordination challenges, including in the area of commerce. At the same time that the Caspian’s very existence is threatened, it has simultaneously emerged as a centerpiece of international efforts to develop trade corridors that avoid Russian and Belarusian territory. Advocates for the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route, also known as the Middle Corridor, emphasize its geopolitical value but also its development potential for integrating the goods-movement economies of Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Southeastern Europe. The World Bank has just completed a comprehensive analysis of the corridors’s potential which focuses on addressing its current limited railway and seaport capacity, lack of unified tariff processes, and a lag in the digitalization of ports. Nevertheless, the far more fundamental threat to the Caspian Sea’s long-term viability as a navigable water body and the contribution that desalination might have to this process have been largely overlooked. A decline in Caspian Sea water levels will, in turn, restrict the size of vessels that can sail in the Caspian Sea, thus aggravating congestion in the ports and the economic viability of trans-Caspian cargo services. In short, the invasion of Ukraine and the resultant reorientation of supply chains has highlighted the Caspian Sea’s importance at the time of its most vital challenge.

Quantifying the Threat

Photo description: The coast of Awaza in Turkmenistan. The rapid drop in sea level has resulted in dramatic shoreline changes. Photo Credit: Citizen of Turkmenistan who wishes to remain anonymous.

In addition to desalination, Caspian water loss is driven by many other endemic factors, including mismanagement of inflow rivers and increased evaporation due to climate change. According to the global Food and Agriculture Organizations' (FAO) AQUASTAT database, the total capacity of dam reservoirs is 223 km3, which is equivalent to >75% of the total discharge to the CS and is primarily located in the Volga River watershed. For example, the Volga-Kama Cascade construction, which produces 25% of Russia's hydroelectricity along the Volga River, substantially curtailed river inflow. In addition to speeding evaporation, the improper disposal of brine from desalination threatens to disrupt the fragile salinity balance of the Sea, imperiling local fishing-dependent economies. Hydrogen production from Caspian seawater, an even more recent development, presents one more competing suitor for this increasingly tenuous resource.

Untreated brine discharge from desalination or hydrogen production can cause further eutrophication akin to the Aral Sea, adding to the Sea’s existing threats by oil and gas byproducts. It can also have negative impacts on the health of nearby populations because the heavy metals on the seabed, which can be spread by wind, contribute to high incidents of respiratory illness and impairments, eye problems, and throat and esophageal cancer in the Caspian-adjacent region.

Brine disposal onto the surface of water bodies can cause biochemical alterations, such as increased water temperature and the accumulation of metals that can threaten ecosystems in the receiving water. At the same time, brine underflows deplete oxygen from receiving waters, which, in combination with high salinity, can have a significant negative impact on sea life.

Caspian Sea Level Fluctuations and Their Impact on Ecosystems, Economy, and Trade

The West is not the only party turning to the Caspian for its political potential. Russia has recently increased its reliance on the Caspian to facilitate a “sanctions-proof” rise in trade with Iran. Through June 2023, Iran imported about 740,000 tons of grain from Russia—a 1.5-fold increase over last year and a 2.5-fold increase over 2021 – simultaneously raising suspicions of covert weapons shipments. Thus, despite the assumption that Russia will oppose the Middle Corridor, its interests are also not immune to the Caspian’s ecological precarity.

Furthermore, the traditional economy of the Russian Republic of Dagestan heavily depends on the Caspian fishing industry, which contributed 17.2% to the Republic’s GDP in 2017. On the border with Chechnya, Dagestan is one of Russia’s poorest regions and was home not only to some of the most intense anti-mobilization protests but also to a rise in anti-government revolts over chronic water shortages. This unique confluence of events should make it clear that the environmental and economic challenges of the Caspian can no longer be compartmentalized.

Resolving the Caspian’s Governance Challenge

The demarcation of the Caspian Sea among the littoral states became controversial after the Soviet Union collapsed. If the Caspian were to be referred to as a “lake,” then its bordering countries would share the lake’s surface and bed equally. Whereas if it were referred to as a “sea,” then the Sea's surface and bed are allotted to the nearer shore per the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. Iran, which has the shortest coastline, claimed the Caspian was a lake. According to this arrangement, the country receives one-fifth of the reservoir instead of one-eighth that would be allocated if it were defined as a sea. Defining the Caspian Sea as a sea is contrary to Russia's interests because it allows the construction of the TransCaspian Gas Pipeline (TCGP) through the Caspian from Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan to Azerbaijan and, finally, Europe. TCGP can provide a viable non-Russian source of natural gas to help the European Union’s energy transition without violating the European Green Deal's principles, which proved to be especially needed during the sanctions placed on Russia due to its war on Ukraine.

After decades of disputes over whether the Caspian should be defined as a lake or a sea, the 2018 Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea finally determined that the Caspian should have a “special legal status.” Article 1 of the Convention defines the Caspian Sea as a ‘body of water surrounded by the territories of the Parties.’ Due to this ambiguous definition, the Caspian is neither referred to as a sea nor a lake. As such, neither the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea nor customary international rules regarding international lakes apply.

The Convention lays the groundwork for bilateral (or multilateral) agreements between Caspian Sea states without the risk of one state sabotaging collective action. While the agreement marked the beginning of a more cooperative environment around the Caspian Sea, it is still unclear how the seabed, which contains most of the oil and gas reserves, will be divided. Article 8, rather, states that “delimitation of the Caspian Sea seabed and subsoil into sectors shall be effected by agreement between States with adjacent and opposite coasts, with due regard to the generally recognized principles and norms of international law.”

In addition, the Convention does not systematically address the Sea’s myriad environmental challenges or create a framework for collective action on either commerce or environmental issues. While the Convention acknowledges the importance of environmental protection, it does not provide clear guidelines on how to achieve this goal. This lack of specificity hampers effective environmental management and can lead to a fragmented approach to dealing with environmental challenges. In a newly published article in the Central Asian Journal of Water Research, we lay out some initial considerations for merging the Caspian’s interdependent environmental and economic challenges within a single governance framework.

With five stakeholders, Caspian governance is almost a textbook case of the potential for a tragedy of the commons. As such, the Sea’s increasingly complex environmental challenges and the infrastructure deficits needed to realize its trade corridor potential point to the need for a unified approach. As the bargaining power of the traditional regional hegemons, Iran and Russia, have decreased, the other littoral states are ramping up their infrastructure investments for the development of the MC. This is the moment to reevaluate Caspian governance to include environmental challenges, address the ambiguous treaty language on desalination and transboundary rivers, and make the Caspian a future example of effective Caucasian-Central Asian coordination.

For more information, read the full article here.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are not necessarily representative of the views held by the Caspian Policy Center. The opinions and statements presented in this article are those of the individual author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official stance or beliefs of the Caspian Policy Center. We encourage diversity of thought and value the expression of various perspectives. The article is intended to provide information and provoke discussion, but it should not be interpreted as an endorsement of any particular viewpoint.

Authors:

Nathan Hutson, PhD is an Assistant Professor of Urban Planning at the University of North Texas. He is a specialist on Eurasian trade integration and recently co-authored a plan for the reconstruction of Mariupol through the Ro3kvit Urban Coalition for Ukraine.

Jahan Taganova is a Climate Resiliency Senior Specialist at the City and County of Denver. She graduated with a joint-degree MS in Water Cooperation and Diplomacy between the world-renowned IHE Delft Institute for Water Education, UN Mandated University for Peace, and Oregon State University.

Rachana Mattur, a civil engineer, holds a master’s degree in Water Management and Governance, specializing in Water Conflict Management. Her research focuses on youth engagement, transboundary water management, gender equality, and solution-oriented climate research.