Double-Landlocked Uzbekistan’s Active Push for Maritime Trade Access

Recent Articles

Author: Justin Rich

06/15/2021

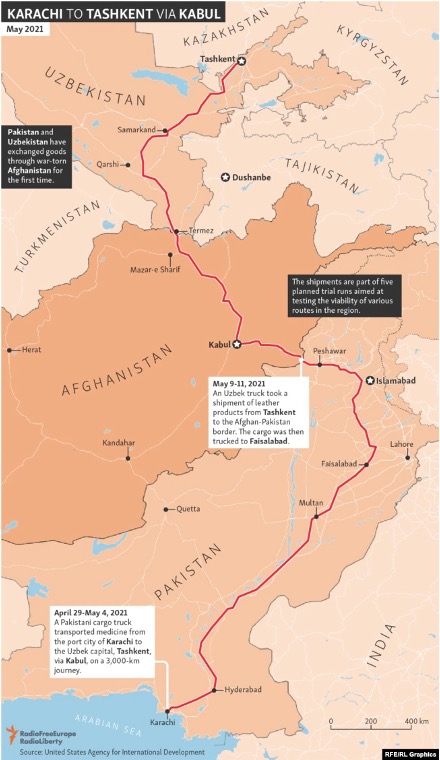

Uzbekistan, Pakistan, and Afghanistan have been in talks that began in February to improve the movement of goods between Central Asia to the Arabian Sea. A pilot program has been successful in transporting medical supplies to Uzbekistan and leather to coastal Pakistan, but the focus is on a much more ambitious project: linking Uzbekistan, one of two double landlocked countries, via a new rail link across a portion of Afghanistan to ports in Pakistan. Currently, trucks are the primary form of transportation across Afghanistan. Trilateral discussions are ongoing, and all three parties have shown interest in pursuing the infrastructure project. However, it is a long way from being realized and the reports that Uzbekistan and Pakistan have been talking about the roadmap with both the Afghan government and Taliban representatives underline some of the complexities such a project needs to address. At the same time, Uzbekistan and Pakistan have discussed ways to address the need for improvements in customs and other regulations and procedures critical to improving the flow of trade with an eye to signing an agreement in July.

RFE/RL

The proposal under consideration would look to build a new railway from Mazar-e-Sharif, in Afghanistan and close to the Uzbekistan border, to Peshawar, where it would link into the Pakistani network. Existing rail networks in conjunction with a rail-link costing $5 billion by some estimates would grant Uzbekistan closer, more affordable access to seaports without having to go through Iran. Port costs via Iran are reportedly two times those in Pakistan. The rail link would also shorten transit time from around 35 days to three to five days with substantial cost savings. Moreover, proponents have noted it can link up with lines running through Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, further improving connectivity in the region.

Despite the potential benefits in terms of lower port costs and significantly improved efficiencies that a completed trans-Afghan railway would bring, there are several tough factors including geography, funding, and Afghanistan’s domestic political situation facing the project’s realization. Constructing a railway through Northern Afghanistan would mean taking the area’s mountainous terrain into account as well as the region’s security implications. Secondly, the Asian Development Bank, through the Central Asian Regional Economic Cooperation program, has already been funding major regional infrastructure projects. The question here is how the project would fit with CAREC’s creation of six trade corridors, which seek to connect Uzbekistan to Iran more than it does to Pakistan. In addition, the U.S. International Development Financing Corporation has promised $1 billion to enhance regional connectivity, but that initiative could seek to connect Mazar-e-Sharif to Herat in Western Afghanistan via rail. Finally, there is the question of the domestic security situation in Afghanistan following the withdrawal of U.S. security forces. Both Uzbekistan and Pakistan are talking with both the Afghan government and the Taliban in an effort to address this issue, but it is important to note that there was no explicit support for the project forthcoming from the approaches to Taliban representatives.

Uzbekistan under President Mirziyoyev has actively worked to improve relations with neighbors and to open borders to expand Uzbekistan’s possibilities for trade. At the 5th Trans-Caspian Forum held by the CPC in June, Uzbekistan’s Ambassador to the United States, Javlon Vakhabov announced that “we believe now that it is high time to launch the trans-Afghan transportation corridor along the Mazar-e-Sharif-Kabul-Peshawar [route].” Ambassador Vakhabov dedicated a portion of his remarks to highlighting how the envisioned route would benefit Central Asia, Afghanistan, South Asia, China, and Europe by augmenting the existing in-land routes that span the continent as well as others that are planned. While the future of the railway is all but certain, the role of trade using trucks under the Transports Internationaux Routiers Convention, which assists in standardizing customs and trade logistics, is a means to boost trade between Central Asia and Pakistan.

Afghanistan has been working to realize new surface routes for accessing international markets, like the Lapis Lazuli Corridor which supports trade from the Afghan-Turkmen border across the Caspian Sea to Europe. With the withdrawal of U.S. security forces, increased potential for trade will be important, although domestic politics will undoubtedly affect Afghanistan’s economic prospects. Further financial involvement could be the way through which the U.S. government supports the Afghan government without a military presence. The railway, while offering benefits to each of the parties, has the potential to be a logistical and financial burden, which may be the factor that ultimately determines its fate. The future of a railway from Tashkent to Gwardar and Karachi is possible, but all parties should be ready for a costly and protracted effort.

Photo Source: Gulf News