Strengthening Central Asian Sovereignty: Diversifying Uzbekistani Remittance Origins

Recent Articles

Author: Jack Halsey, Nassim Ali Ahmad, Caroline Southworth

10/31/2025

As Central Asian states continue to take steps that decouple themselves from Russia, it is essential that regional policymakers not only establish new trade relations but also diversify labor migration destinations. Through government-maintained foreign job boards and improving local journalistic coverage on migrant conditions in Russia, Central Asian governments can promote a wider assortment of labor migrant destination, decreasing GDP reliance from Russia.

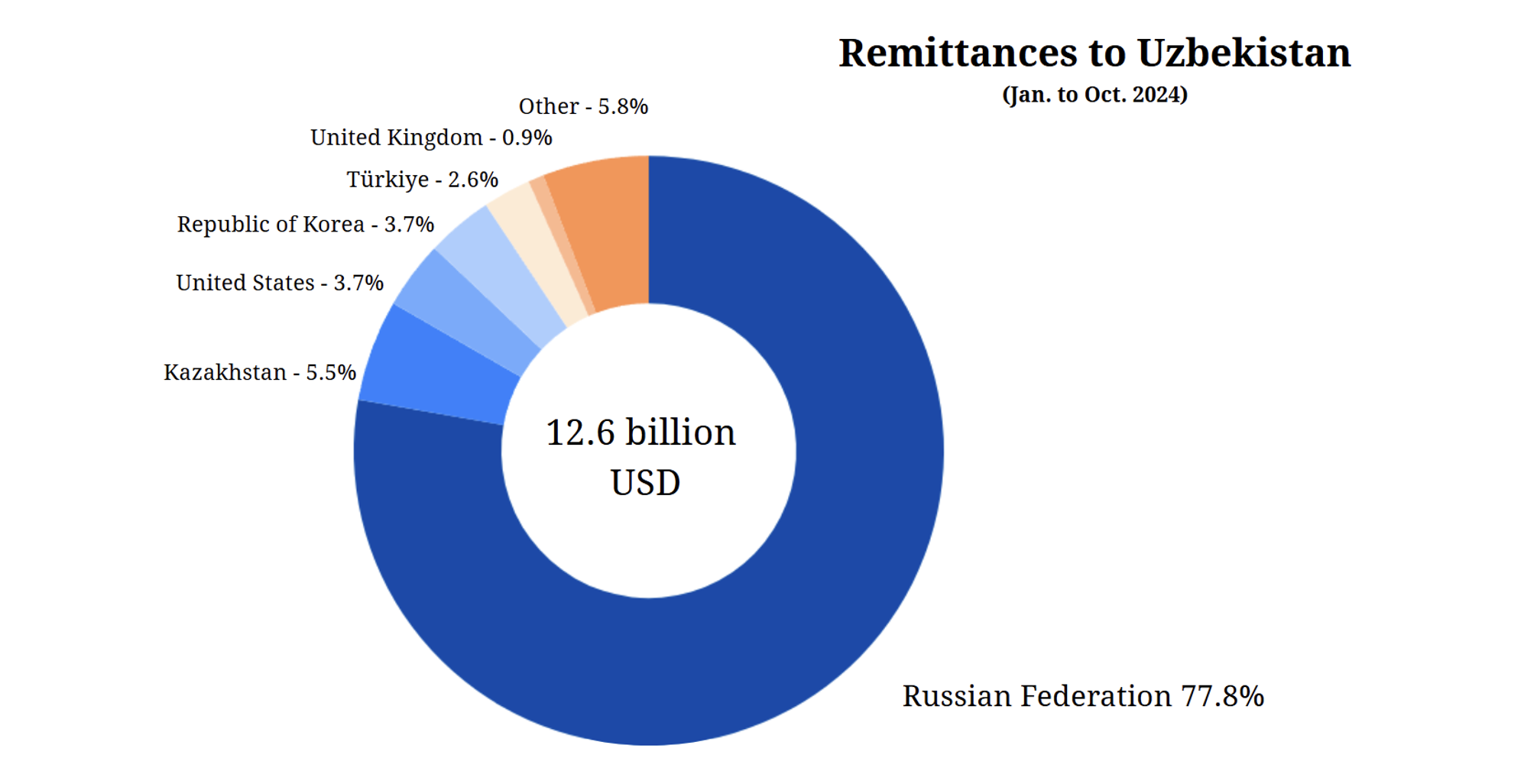

When observing Central Asian remittances, it would seem logical to focus on countries like Kyrgyzstan or Tajikistan, where in 2022, 26.6 percent and 49.9 percent, respectively, of their GDPs entered each country as remittances. However, while remittances only accounted for 17.2 percent of Uzbekistan’s GDP, the sum of $15.51 billion was more than the sum of both Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan’s entire GDP. Therefore, with more money coming into Uzbekistan, there is a better chance to understand where the money is coming from and how it can potentially be shifted.

From a historical and geographical perspective, Russia is the obvious choice for Uzbekistani labor migrants. Although Uzbekistan and Russia do not share a border, it is closer and more easily accessible destination compared to China. Also, Uzbekistani labor migrants are more likely to speak Russian, about 18 percent of the population, rather than Chinese or any of the other regional languages. Over 55 percent of all labor migrants in Russia are from Uzbekistan, in part, due to the conditions listed above.

From a historical and geographical perspective, Russia is the obvious choice for Uzbekistani labor migrants. Although Uzbekistan and Russia do not share a border, it is closer and more easily accessible destination compared to China. Also, Uzbekistani labor migrants are more likely to speak Russian, about 18 percent of the population, rather than Chinese or any of the other regional languages. Over 55 percent of all labor migrants in Russia are from Uzbekistan, in part, due to the conditions listed above.

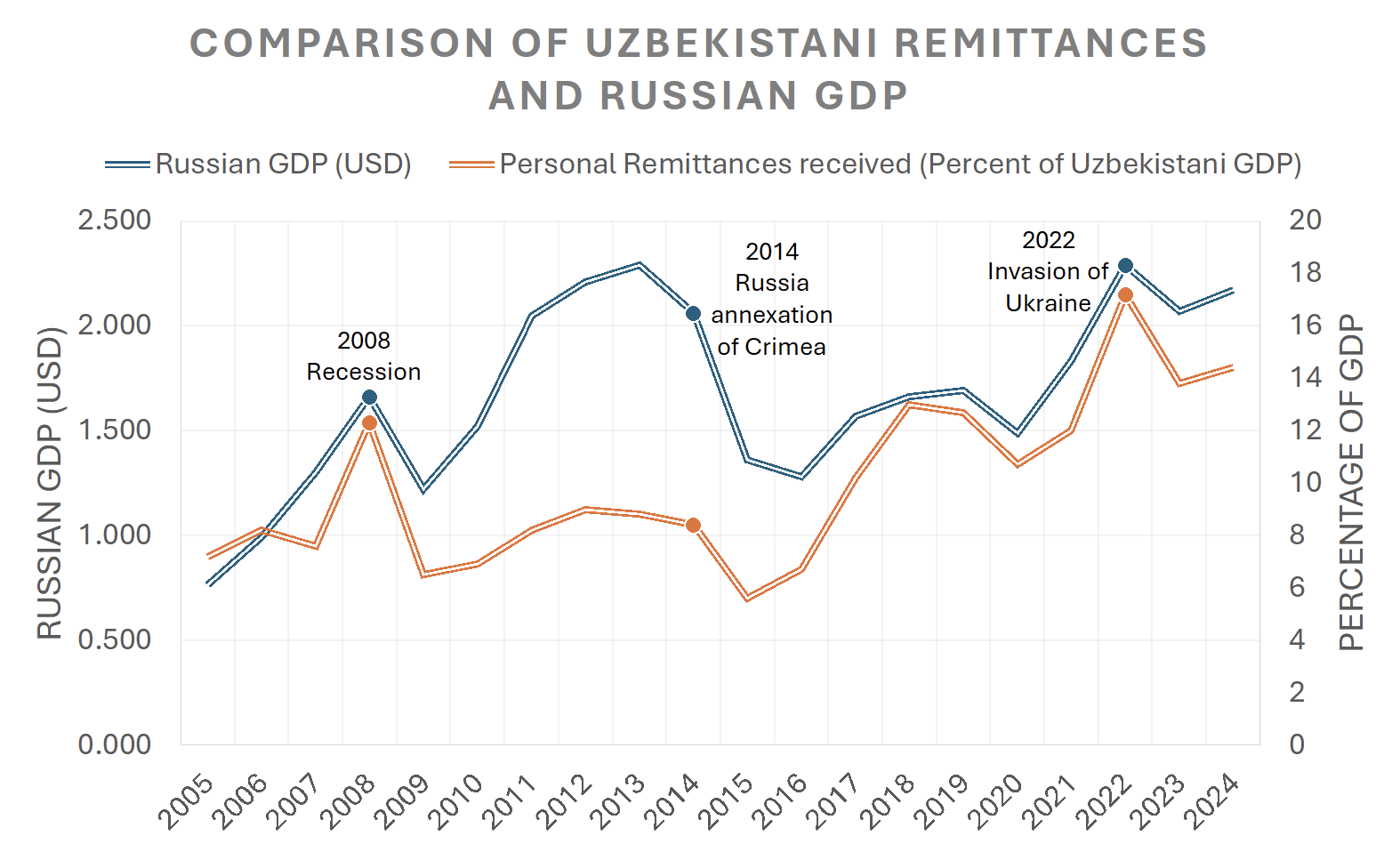

Considering that a majority of Russia’s migrant labor is from Uzbekistan, and nearly 78 percent of Uzbekistani remittances originate from Russia, a tangled relationship is born, where the Uzbekistani economy is vulnerable to the ebbs and flows of the Russian economy. The graph below tracks Russia’s GDP as well as Uzbekistani remittances as a percentage of its GDP. With slight variances, the general shape and inflection points are clear. When Russia faced economic crises, whether from global phenomenon (2008) or self-made (2014 and 2022), Uzbekistan’s receipt of remittances faced similar crashes. These inflection points are evident when looking at

other Central Asian countries as well, especially Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. Regarding Kazakhstan, even though a significant portion of Kazakhs travel to Russia for work, remittances ranged from 0.1 to 0.3 percent of Kazakhstan’s GDP between 2005 and 2024. If having one’s economy severely impacted by the actions of a foreign government are not enough to sway policymakers to promote other labor destinations, there have also been high rates of Islamic radicalization. This radicalization, reinforced by Russia’s poor labor conditions and worsening political climate, has led to thousands of Central Asians joining jihadist groups in the Middle East over the last decade.

*Russian GDP is in trillions of dollars. Data source: World Bank

Therefore, Central Asians policymakers need to combat Russia’s strong pull factors. To accomplish this, we have two policy recommendations. First the Uzbekistani government should work with U.S. Embassy Tashkent on targeted technical assistance to bolster the capacity of the Agency for Migration (formerly Agency for Foreign Labor Migration) and its flagship “Jobs Abroad” platform. Currently, there are domestic initiatives (for example, vocational training and language courses) aimed at improving Uzbekistani workers’ competitiveness abroad, in hopes of promoting the diversification of labor destinations. The “Jobs Abroad” platform has manifested significant changes in orthodox labor pathways: only 0.15 percent of labor migrants traveled through official channels prior to the implementation of the program whereas the figure has jumped to 9 percent since 2022 and continues to rise. Despite facing supply-demand mismatches with over 2 million users and around 50,000 available jobs, the platform signals early successes in reducing informality and Uzbekistan’s willingness to adapt.

Our second recommendation focuses on strengthening local media in order to increase awareness of discrimination against labor migrants in Russia, widespread abuse, and poor working conditions while highlighting alternative destination countries, like South Korea and Türkiye. For the United States, the Uzbekistani government could work with the U.S. Agency for Global Media to shift resources from underperforming legacy media platforms toward a local journalism grant program, ideally administered through a proxy, such as Transparency International or a comparable civil society intermediary. However, following U.S. President Donald Trump’s federal budget cuts, the agency’s ability to support Uzbekistan has been limited. These decreases in funding could therefore be supplemented by an EU program. Similarly, the European Commission has already launched a project, the Central Asia Resilience & Empowerment for Media (C.A.R.E.), in Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan.

The final hurdle that policymakers face is convincing countries like the United States as well as the EU that they benefit from assisting in the redirection of labor migrants from Russia. The simple answer is that by decoupling Central Asian economies from Russia, each individual economy will become more secure and become more predictable based on its own decisions rather than the actions of a foreign body. American and European companies remain wary of investing into the region due to its, at times, unpredictable business environment. If Central Asian policymakers could reduce that risk and create a more welcoming environment, they could continue to diversify their economies in the international market.

With the continuation of the war economy in Russia, Moscow’s economic future is still up in the air. The war has also played an important role in keeping the Kremlin’s focus away from Central Asia. If Central Asian policymakers were to make a play to influence and shift labor migrant flows, this would be the time to do so. Whether in future UNGA sidebar meetings like the C5 +1 with the United States, or ministerial meetings, Central Asian policymakers should convince and work with other international organizations to strengthen their international job forum websites and increase reporting on labor migrant work conditions in Russia. In doing so now, Central Asia will not only decouple itself faster, but it will also avoid any shared economic stresses that the Russian economy is likely to face due to a continued conflict.