Russia On the Back Foot in the Black Sea: Implications for Georgia and the Caspian Region

Recent Articles

Author: Nicholas Castillo

01/31/2024

Russia has been forced to shift tactics in the Black Sea. Since the beginning of the war in February of 2022, Ukrainian armed forces have destroyed or damaged nearly a third of Moscow’s once-commanding Black Sea fleet using missile strikes and unmanned “drone boats.” In one instance, on December 26, 2023, Ukraine struck a Russian tank landing ship on the eastern coast of occupied Crimea, triggering a mass explosion. Ukrainian armed forces have now effectively driven most of the Russian fleet out of occupied Crimea, with the Institute for the Study of War reporting that Russia has steadily moved above and below surface naval vessels from Crimea to an alternative port in Novorossiysk, on Russia’s Black Sea coast, between June and December of 2023. Russia’s retreat from the west of the Black Sea suggests mixed consequences for the Caspian region, providing definite security threats alongside uncertain commercial ramifications.

For Ukraine, Russia’s downgraded presence has been both a military and economic victory. Militarily, Ukraine undeniably gains a strategic edge as it shapes the maritime battlefield. This includes not only attacks on ships but critical aerial crafts such as the A-50 and Il-22M surveillance and command planes, rare and expensive tools. On January 15, Ukraine destroyed one of each in a single day, likely blinding Russia in the Northeastern quadrant of the Black Sea. Economically, however, Ukraine may have won a more important victory; significantly downgrading Russia’s capacity to threaten its southern ports with blockade and the vital grain shipments that exit Ukraine by way of the Black Sea. Recent reporting on the surprising buoyancy of Ukraine’s economy speaks to the importance of freeing up ship-ways for Ukraine. However, Russia’s newfound defensive posture in the Black Sea does not necessarily bode well for the states of the Caspian region.

Georgian Implications

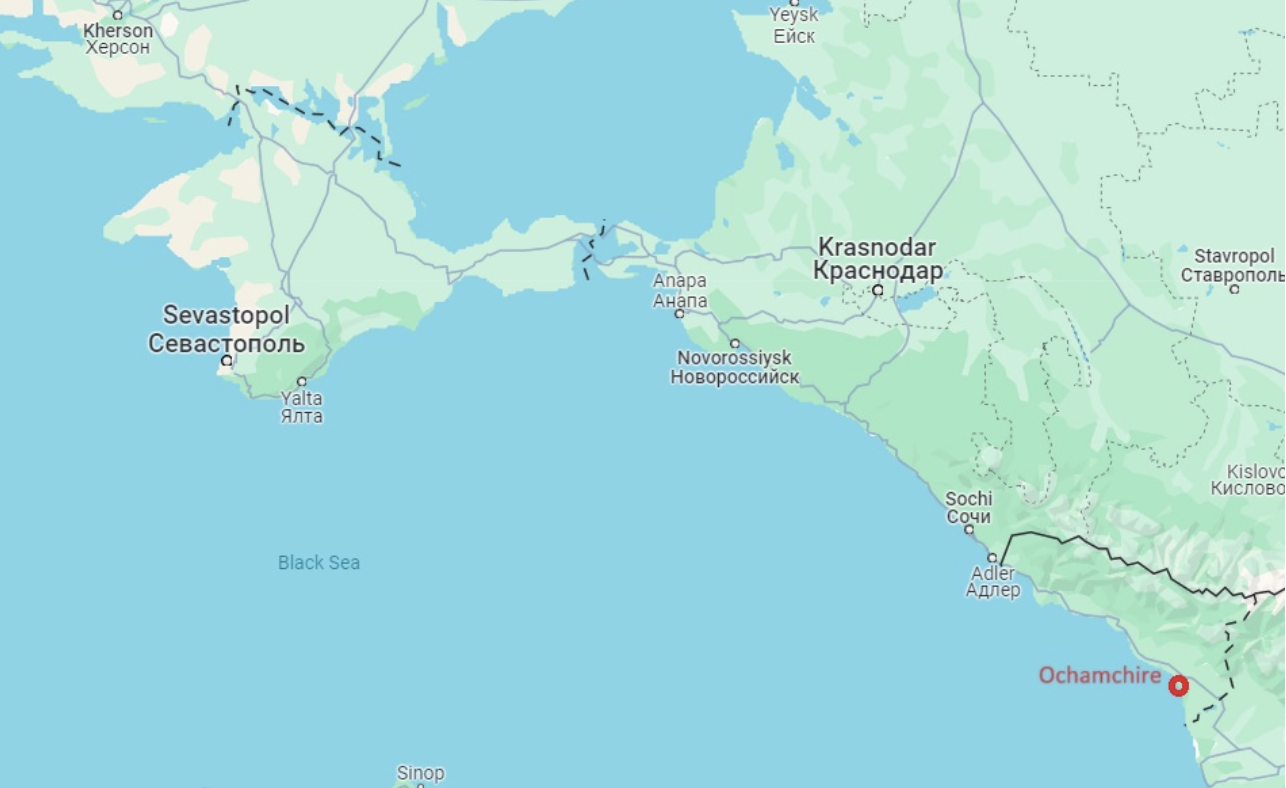

Of the South Caucasus countries, Georgia will feel the most immediate consequences of Russia’s Black Sea retreat. On October 5, Russia and the Russian-occupied Republic of Abkhazia announced an agreement allowing Russia to construct a permanent naval base in the district of Ochamchire on the Black Sea coast, a base that will likely house Russia’s displaced Black Sea fleet. Ukrainian intelligence reported on October 23 that Russia had begun dredging the area, prepping to establish a large naval base. Abkhazia, an internationally recognized region of Georgia, broke away from Tbilisi in a war following the collapse of the Soviet Union and since has been administered by Russian-backed separatist authorities. Moscow has steadily integrated the territory militarily, politically, and economically – a situation of de-facto Russian occupation.

Photo courtesy of Google Maps

Although, for the moment, Russia’s Novorossiysk port is a safer location than Crimea, it does not provide complete safety for Russia’s fleet. Ukrainian forces are able and willing to strike Russia’s internationally recognized territory and, in fact, Ukrainian armed forces in August launched a successful drone ship attack on the Novorossiysk port. If the Ukrainians achieve a breakthrough in Zaporizhya oblast, attacks such as these could become much more common and more intense. Ochamchire, a much farther destination that Ukraine is likely unable or unwilling to attack, therefore represents a much more secure long-term location for Russia’s Black Sea fleet.

Even if Ukraine was logistically able to strike Ochamchire, by placing its navy in what is internationally recognized as Georgian territory, Russia complicates Ukraine’s military decision-making process. Ukraine may not be willing to stir controversy and drag Georgia, a fellow European Union candidate, into this war by attacking its territory. However, President Zelenski has indicated Ukraine may be willing to strike the Russian fleet there.

Additionally, Georgia’s own maritime plans may be disrupted by the construction of a Russian base at Ochamchire. Georgia has long hoped to build a large commercial port at Anaklia, one that would take advantage of Georgia’s position within the Middle Corridor and Black Sea coast. However, Anaklia is only 35 kilometers to the south of Ochamchire. The prospect of a Russian military base being so close, one that might at some point come under fire, could complicate construction, deter investment, and raise insurance rates for ships crossing through the area.

There is another, more consequential, motive that might have factored into Moscow’s decision to construct the naval base in occupied Abkhazia. Establishing the base in Ochamchire came amidst discussion by both Abkhaz and Moscow-based elites over the annexation or integration of Abkhazia into Russia or a Moscow-centered Union State. This was followed up by a controversial agreement to transfer a local Abkhaz resort to Russia. Under this agreement, for an annual price of one ruble per land parcel, Russia will “rent” the Bichvinta complex of holiday homes and the land it sits on for 49 years. This agreement has been criticized as “another land grab by Russians in Georgian territories.”

Even though Abhkazia has housed a Russian military base since 2008 and Russia has distributed its own passports there since 2002, the construction of a mass naval base will tie the region to Russia and its security interest to a much greater extent than before. It is possible that constructing its central Black Sea naval base in occupied territory is part of Moscow’s preparation for formal annexation of Abkhazia, or at least strengthening the justification for that option, if the Kremlin chooses to pursue it at some point. With an expected construction time of at least three years, the Ochamchire base is, therefore, less of an imminent threat to Ukraine and more of a long-term threat to Georgia.

Region-Wide Commercial Interests

Russia’s downgraded military power in the Black Sea could entail benefits for the Caspian countries invested in the Middle Corridor transit route. For years, Russia has engaged in a variety of malign practices impacting commercial shipping. Russia’s invasion itself caused chaos, freezing traffic in the earliest months of war and causing a long-term spike in the cost of insuring commercial ships. Russia has continually attacked Ukrainian commercial infrastructure on the southern coast, pulled out of agreed-upon maritime deals, most notably the 2022 grain shipment deal, and directly threatened private commercial ships that crossed the Black Sea on their way to Ukraine, forcing them to take longer routes along the European coast. Russia has used control over trade routes to punish Caspian states, disrupting Kazakh oil shipments running through Russia and the Black Sea throughout 2022 in reaction to Astana not supporting the war on Ukraine. Therefore, downgrading Russia’s ability to project power across the Black Sea may be a net positive for the region, bringing down the ability of a rogue state to influence commerce.

However, it is not yet certain that the recent contestation over the Black Sea will have positive consequences for maritime commerce writ large. It is unlikely that Russia will simply give up its dominating presence over the Black Sea. The region is important for Russia’s access to the Mediterranean and it borders strategically significant countries, two of which Russia is currently occupying – Ukraine and Georgia. Ukraine’s lack of naval battleships means there will likely be no open ship-to-ship conflict in the Black Sea, but drone boat attacks and missile strikes will likely continue, possibly threatening the Novorossiysk port – a port still vital to Kazakh energy shipments. Russia’s current deterred position may simply lead to more counterattacks, including on Ukraine’s civilian infrastructure along the coast. Russia’s new port in occupied Georgia could likewise impact the long-term build-out of the Middle Corridor by adding a layer of difficulty to constructing a port at Anaklia.

At the least, Russia’s recent defeats in the region do not yet seem to entail an immediate resumption of normal commercial traffic, given that there is no end in sight for fighting over the Black Sea. Attacks on naval infrastructure throughout 2022 and 2023, in fact, led to an increase in the price of insuring some commercial vessels in the Black Sea – although this mainly affected Russian and Ukrainian ships. Ukraine did, however, manage to reach a deal with insurers in November to bring down the cost of grain shipments.

In the long run, Russia’s recent retreat in the Black Sea could be a net positive for the countries that border the sea. For years now, security experts and elites have fretted over the Black Sea becoming a “Russian lake,” as Türkiye’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan put it in 2016. Yet in the short to medium term, the picture is less clear. Russia’s recalibrated posture in the Black Sea will bring more security threats to de jure Georgian territory, and it does not necessarily entail a return to normalcy for Black Sea shipping. This will likely remain the case until there is either a total naval victory over Russia in the region or a complete re-vamping of Russian military practices – neither of which looks likely for the near future.