The Climate Crisis has come to the South Caucasus

Recent Articles

Author: Zachary Weiss

07/29/2024

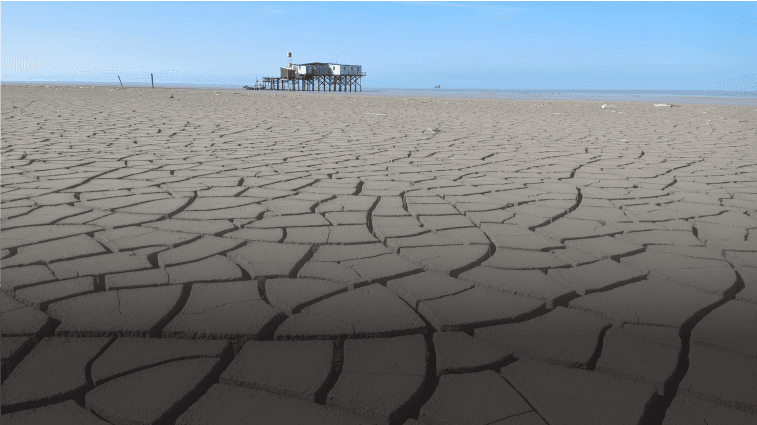

Climate change has begun to harm the physical and economic security of people living in the South Caucasus, and the trend is only worsening. The frequency of natural disasters such as mudslides, droughts, and floods have increased, affecting huge swaths of land, including population centers. Water sources across the region are diminishing. Crop yields are increasingly unpredictable. While Azerbaijan, Armenia, Georgia, and have taken some steps to mitigate climate change, they have so far struggled to adapt fast enough to the new environmental realities evidenced in changing water supplies, an increasing variety of natural disasters, and weather anomalies that their populations face.

Water Issues

As climate change worsens globally, extreme weather events, including heavy rainfall, are expected to increase in frequency. Earlier this year, a flood resulting from heavy rainfall killed three people and forced hundreds to evacuate from their homes in Northern Armenia alone. Bridges, homes, and roads were destroyed, and hindered water supply to local settlements. While extreme rainfall events have killed and will continue to kill and displace people, as well as damage infrastructure, the South Caucasus faces a more immediate concern in the negative impact that is resulting from a lack of rainfall and water shortages.

Parts of the South Caucasus are already experiencing reduced supplies of water, and the risk of further water insecurity presents a risk to a significant portion of their populations’ employment, as well as to the economies of each country. In the South Caucasus, higher temperatures are hastening glacial recession which is a factor that threatens regional water supplies, as well as the safe consumption of downstream water. Although Georgia is home to more glaciers than Armenia and Azerbaijan, Georgia’s declining icepack feeds into the falling water sources of these other countries. As a result, people in the entire region are affected by the Georgian glacial recession.

In parts of Azerbaijan, glacial runoff makes up a significant portion of the country’s potable water supply. Emblematic of global trends, glaciers supplying Azerbaijan with drinking water are receding, forcing the Caspian littoral country to contemplate other options. The country is also increasingly experiencing flood and drought extremes, resulting in researchers labeling Azerbaijan “highly sensitive” to climate change.

Natural Disasters

Rising temperatures are a root cause of many natural disasters in the Caucasus that are increasingly associated with climate change. In Armenia alone, the average temperature has increased by about 1.23 degrees Celsius between 1929 and 2016. Azerbaijan experienced a similar increase by 2010 compared to temperatures between 1961 and 1990. In Georgia, data suggests temperature increases have been less significant but have the potential to worsen in the coming decades.

One of the major objectives of the 2015 Paris climate accords is to limit temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius globally. Projections for the Caucasus estimate that by 2040 average regional temperatures could increase by an additional 1.3-1.7 degrees Celsius, resulting in upwards of a cumulative 3.0 degree Celsius rise. With its knock-on effects for water scarcity and drought, this temperature change could cause devastating impacts on the region’s environment and long-term habitability.

Wildfires in particular become more pervasive with higher temperatures: Armenia and Georgia have experienced several significant wildfires in the past decade, a trend that will only continue with climate change worsening. In one example, a 2017 wildfire in Armenia ran through 320 hectares of land, and required the labor of hundreds of people to halt the spread.

Other natural disasters have been increasingly frequent in the South Caucasus, partially due to climate change (particularly through changes in temperature and precipitation). Some of the most impactful have included mudslides and landslides. The village of Chambarak in Northeastern Armenia, for instance, was routinely and increasingly hit with mudslides, which were particularly harmful to the village’s agricultural and livestock infrastructure. The UNDP aided the village in the winter 2022 by building walls to protect the village, as well as special channels to divert the slides.

Almost a third of Armenia is at similar risk for disasters, as many villages and communities do not have these crucial infrastructure improvements. In Georgia, about 70% of the country is at risk of similar mud- and landslide hazards, though in Azerbaijan only about eight percent of the population lives in areas that are affected. The slides are often caused by glacial erosion which bares and destabilizes formerly frozen soils once covered by ice, and these slides are compounded by the increased run-off from glacial melt.

Weather Anomalies and Drought

Too much and too little rainfall are other increasingly common sources of natural disaster for the region. People in the South Caucasus rely on predictable flows of water for employment. With half the population of Georgia and more than a third of Armenians and Azerbaijanis employed in the agricultural sector of their respective economies, projections of reduced or unpredictable precipitation over coming decades could worsen conditions for agricultural production of wheat and corn, with potentially significant declines in crop yields. As Azerbaijan has begun efforts to diversify its economy, maintaining agricultural land is a necessary step. Those aspects of climate change that hinder agricultural production are a threat to both the country’s industry and food security.

Just as too much rain, increasing drought, and glacial runoff are climate-change indicators for the region, a key byproduct of the South Caucasus’s growing environmental imbalance concerns the Caspian Sea. The body of water that connects Azerbaijan to Central Asia is experiencing historically declining water levels, with predictions of further decline by the end of the century of up to a quarter of the sea’s surface area. Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Iran, and Turkmenistan have all built beach-front desalination plants to supply populations with safe drinking water from the Caspian Sea. Like many contemporary efforts to address climate change, these efforts to provide drinking water are impacting water levels that could render some of these plants too far from the ebbing sea water and, therefore, useless.

As the COP29 conference in Azerbaijan nears, countries in the South Caucasus will likely showcase their actions to combat climate change, thus far, and engage in multilateral agreements to curb it further. For example, Azerbaijan’s Deputy Foreign Minister recently proclaimed that the second component of the country’s environmental goals included achieving “a green economy.” The Armenian Minister of Territorial Administration and Infrastructure announced in late 2023 that his country was on track for solar energy to reach 15% of total energy output by 2030. Georgia approved a climate change action plan in March of 2024 with investments valued at over $1.3 billion, including efforts that would protect the agricultural sector and reduce emissions. But as citizens of Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Georgia are already facing threats to the region’s physical and economic security, the three nations would be wise to go beyond just reducing their carbon footprints to address the impact of today’s evolving climate realities that are already threatening their populations. They need to look for broader solutions while there is still time.